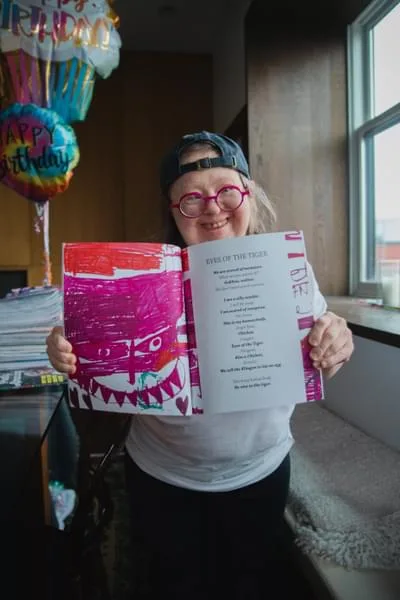

Teresa Heartchild describes herself in many ways – a “self-activist,” a “wounded daughter,” and perhaps most importantly, an artist. Teresa lives in the Gastown neighbourhood of Vancouver with her sister Franke and brother-in-law Bill. A view of the Salish Sea, with its ever-present tankers and watchful mountains, inspires her to create illustrations and poems. She has published two books of her work and mounted exhibitions at galleries in Canada and internationally. One of Teresa’s pieces, entitled Wind Warning, is hanging in the Inclusion BC office in New Westminster.

Teresa Heartchild describes herself in many ways – a “self-activist,” a “wounded daughter,” and perhaps most importantly, an artist. Teresa lives in the Gastown neighbourhood of Vancouver with her sister Franke and brother-in-law Bill. A view of the Salish Sea, with its ever-present tankers and watchful mountains, inspires her to create illustrations and poems. She has published two books of her work and mounted exhibitions at galleries in Canada and internationally. One of Teresa’s pieces, entitled Wind Warning, is hanging in the Inclusion BC office in New Westminster.

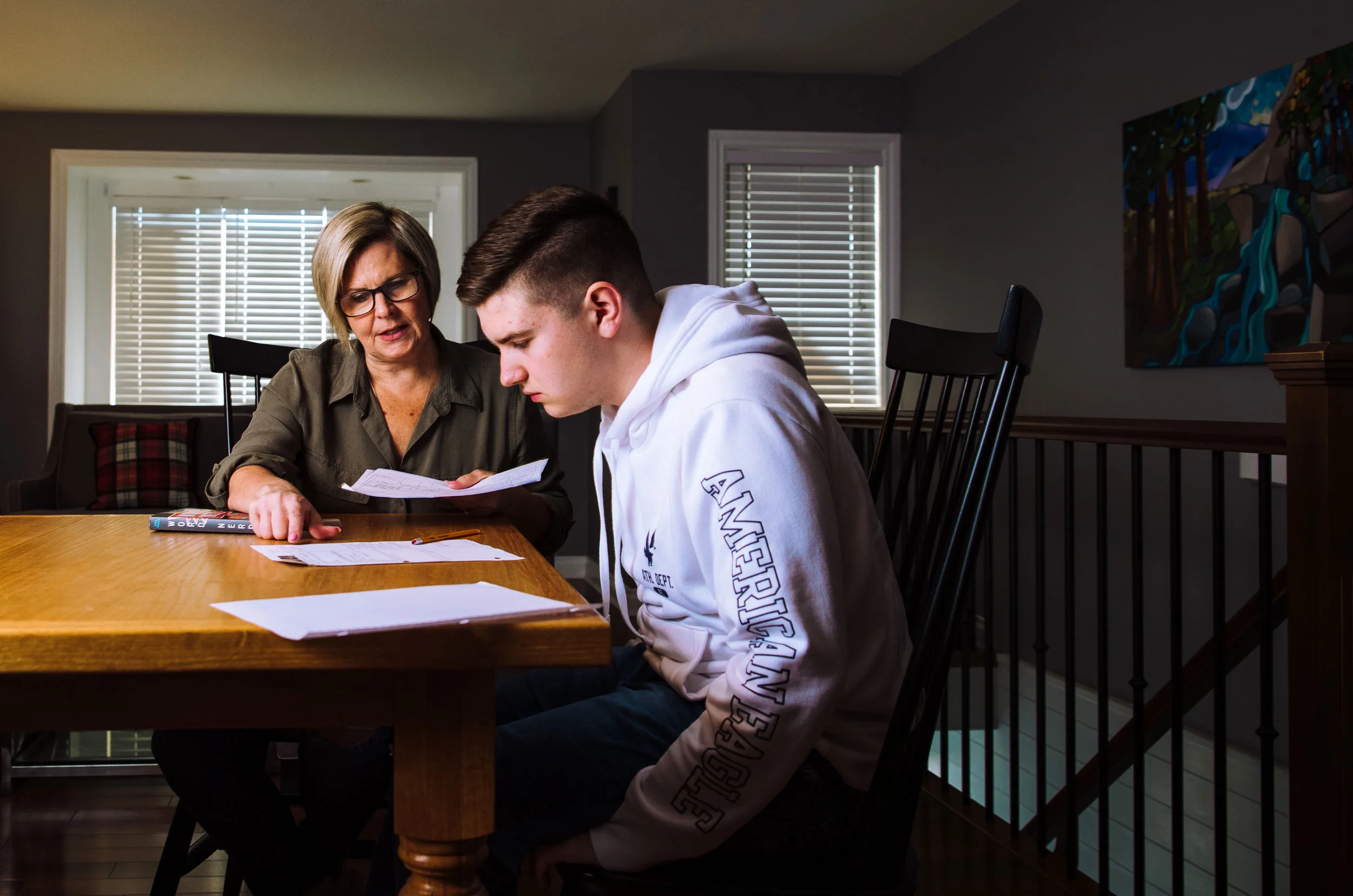

Arriving at the apartment Teresa shares with her sister and brother-in-law, she seems to be precisely where she belongs. She sits at a dining table, surrounded by markers, drawing paper and an enormous stack of completed illustrations, of which she is very protective and scolds me for trying to touch them without her permission.

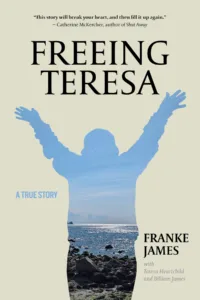

Teresa didn’t always live here, of course. When she was younger, she lived with her parents and siblings. The story of Teresa’s life, and the dramatic conflict that would eventually arise within her family about where she would live, is the subject of a new book entitled Freeing Teresa. She is also a contributor and has adopted the pen name “Teresa Heartchild”. The book is available as a paperback and e-book on Amazon.ca, and will soon be released as an audiobook on Audible.com

Teresa didn’t always live here, of course. When she was younger, she lived with her parents and siblings. The story of Teresa’s life, and the dramatic conflict that would eventually arise within her family about where she would live, is the subject of a new book entitled Freeing Teresa. She is also a contributor and has adopted the pen name “Teresa Heartchild”. The book is available as a paperback and e-book on Amazon.ca, and will soon be released as an audiobook on Audible.com

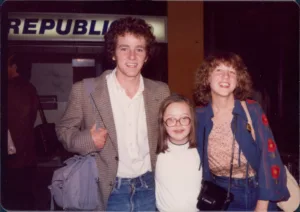

In the ‘70’s, living at home and attending the same school as one’s siblings was an unfortunately remarkable situation for someone with Down syndrome. “When Teresa was born in 1964, my parents were told to put her into an institution, but they refused,” Franke recounts. “They brought Teresa home and said that she would be showered with the same attention and love that the rest of us had.”

“My mother was amazing”, says Franke, “I didn’t realize how special she was at the time, but she was a real trailblazer.” Teresa and her family were featured in a 1979 television documentary about society’s negative perception of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, in which her mother talks about wanting Teresa to pursue her ambitions and build the skills that would allow her to have the life she deserves.

Teresa continued to live with her parents into adulthood, and when her mother passed away in 1999, she moved into a condo with her father: “Dad and Teresa were a team; they really helped each other and it was lovely to see them together,” says Franke. But, as her father got older, his memory was slipping, and some of Teresa’s siblings had concerns about whether this living situation was sustainable. There was disagreement within the family about what should happen next. In November of 2013, against the wishes of Teresa, Franke and their father, Teresa’s siblings placed her into a nursing home at the age of 49. This intensified an already heated conflict within their family, in which one faction believed that this was the best outcome for Teresa – a place where she’d be housed, fed, and clothed – while the other asserted that Teresa deserved more and that her rights were being violated.

What followed was a painful fight over what would happen to Teresa, which involved lawyers, petitions and the police, and resulted in lasting damage to the relationships between Teresa’s family. As Billiam James, co-author of Freeing Teresa (and Teresa’s brother-in-law) puts it, the book is about “Teresa’s right to decide where she lives, and how that right was taken away from her.” This book illuminates ways in which people’s rights have been and continue to be ignored: “It’s the same type of prejudice that some people have about disabled people being in love, or participating in sexual activity, or using money, or voting. There’s a wide swath of the population who think people with intellectual disabilities shouldn’t have these rights,” says Bill. And, as Franke points out, Teresa’s story is not unique; there are thousands of stories like hers. In fact, according to a 2014 report by the Developmental Services Committee, “long-term care homes are pressured to accommodate young and middle-aged people with developmental disabilities without any medical need for this type of care or any training to support this group of clients.”

What followed was a painful fight over what would happen to Teresa, which involved lawyers, petitions and the police, and resulted in lasting damage to the relationships between Teresa’s family. As Billiam James, co-author of Freeing Teresa (and Teresa’s brother-in-law) puts it, the book is about “Teresa’s right to decide where she lives, and how that right was taken away from her.” This book illuminates ways in which people’s rights have been and continue to be ignored: “It’s the same type of prejudice that some people have about disabled people being in love, or participating in sexual activity, or using money, or voting. There’s a wide swath of the population who think people with intellectual disabilities shouldn’t have these rights,” says Bill. And, as Franke points out, Teresa’s story is not unique; there are thousands of stories like hers. In fact, according to a 2014 report by the Developmental Services Committee, “long-term care homes are pressured to accommodate young and middle-aged people with developmental disabilities without any medical need for this type of care or any training to support this group of clients.”

The eventual outcome of the fight to get Teresa out of the nursing home and into an appropriate living situation was that she, Franke and Bill moved together from Ontario to the West Coast, landing first in Victoria, BC. When they moved to BC, they hardly knew anyone, and Teresa was their connection point to new communities. Through her, they met lots of people in the disability community. Franke is a visual artist and environmental activist, and she and Teresa found that making collaborative art together was a new way for them to bond as siblings. It didn’t take long before Teresa was making her own artwork: “We didn’t know that Teresa was so artistic. It was really a wonderful discovery.” After a relatively short stint in Victoria, the trio moved again, this time to their current home in Vancouver, where Teresa applied for her first small arts grant, with support from Bill and Franke. She got it, and from that point forward she has considered art to be her occupation.

The eventual outcome of the fight to get Teresa out of the nursing home and into an appropriate living situation was that she, Franke and Bill moved together from Ontario to the West Coast, landing first in Victoria, BC. When they moved to BC, they hardly knew anyone, and Teresa was their connection point to new communities. Through her, they met lots of people in the disability community. Franke is a visual artist and environmental activist, and she and Teresa found that making collaborative art together was a new way for them to bond as siblings. It didn’t take long before Teresa was making her own artwork: “We didn’t know that Teresa was so artistic. It was really a wonderful discovery.” After a relatively short stint in Victoria, the trio moved again, this time to their current home in Vancouver, where Teresa applied for her first small arts grant, with support from Bill and Franke. She got it, and from that point forward she has considered art to be her occupation.

In addition to her illustration work, Teresa also publishes her poetry, which Franke and Bill support her to record and edit. Like many people with Down syndrome, Teresa talks to herself and to imaginary friends, a tendency that can sometimes be misinterpreted by medical professionals as an indication of mental problems or decreased mental function, but according to research done by the Adult Down Syndrome Centre, is a normal coping mechanism for people to process information or express frustration, and is a behaviour observed in 81% of people with Down syndrome[1]. While lots of people may ignore or dismiss what Teresa says when she self-talks, Franke and Bill found it fascinating: “We started recording it,” Franke describes, “Then we print it out, and Teresa helps us edit the written words into poems.” It’s moving to see Teresa’s unique ways of seeing the world framed as a gift, and her ways of communicating being viewed as art rather than dysfunction.

In addition to her illustration work, Teresa also publishes her poetry, which Franke and Bill support her to record and edit. Like many people with Down syndrome, Teresa talks to herself and to imaginary friends, a tendency that can sometimes be misinterpreted by medical professionals as an indication of mental problems or decreased mental function, but according to research done by the Adult Down Syndrome Centre, is a normal coping mechanism for people to process information or express frustration, and is a behaviour observed in 81% of people with Down syndrome[1]. While lots of people may ignore or dismiss what Teresa says when she self-talks, Franke and Bill found it fascinating: “We started recording it,” Franke describes, “Then we print it out, and Teresa helps us edit the written words into poems.” It’s moving to see Teresa’s unique ways of seeing the world framed as a gift, and her ways of communicating being viewed as art rather than dysfunction.

None of what Teresa has accomplished in the world of the arts could have happened had she stayed in that nursing home in Ontario, and I can’t help but wonder how many other people there are whose gifts and perspectives we’ve been robbed of the opportunity to learn from. “It’s important to get this conversation started, because this is something that most people don’t want to talk about,” says Franke, “It’s frightening how quickly people’s rights are taken away, and the power that doctors and social workers have – they just tick a box and that person can get locked up.”

To see more of Teresa’s art and a history of her advocacy, visit her website at www.teresaheartchild.com

The book Freeing Teresa will be released on October 12, and is now available for pre-order on Amazon

Written and photographed by Galen Exo

Do you enjoy real life stories about inclusion? This article was featured in the latest edition of our monthly newsletter, Inclusion in Action. Subscribe today to receive regular updates with stories like this.

Want to read more? Browse our newsletter archive here