Table of contents > Chapter Five: Individual Education Plans (IEPs)

In this chapter:

- Parent/Caregiver Consultation

a. Resources - The IEP Process

a. Developing an IEP

b. The IEP Meeting

c. Tips for preparing a parent/student report for an IEP meeting

d. Reviewing the IEP

e. Coordinating Other Student Plans with the IEP

e. Including Transitions in the IEP

f. After the IEP Meeting

g. Questions to ask about the IEP

h. IEPs and SMART goals

i. Implementing and evaluating the IEP - Reporting on student progress

- Student Learning Plan (or Student Support Plan)

- Competency-Based Individual Education Plan

a. Presuming Competence

b. Student Agency - Adaptations and Modifications

a. Adaptations

b. Modifications - Academic or Life Skills?

- Graduation Requirements and Transcripts

a. Resources: Adjudication and Exam Adaptations - Graduation: Evergreen Certificate or Dogwood Diploma

- “Grade 13”

- Resources: Individual Education Plans

Individual Education Plans

“An Individual Education Plan (IEP) is a documented plan developed for a student with special needs that describes individualized goals, adaptations, modifications, the services to be provided, and includes measures for tracking achievement” (Special Education Service: A Manual of Policies, Procedures and Guidelines by BC Ministry of Education)

![]() Individual Education Plans for “students with special needs” (see ministry definition of special needs) are a requirement under the School Act, mandated by Ministerial Order 638/95.

Individual Education Plans for “students with special needs” (see ministry definition of special needs) are a requirement under the School Act, mandated by Ministerial Order 638/95.

This order directs school boards to ensure that an IEP is in place for the student “as soon as practical” after a student’s needs are identified. The order requires that the IEP be reviewed at least once during the school year and when necessary, revised or canceled. It also requires that parents, and students where appropriate, must be consulted about the preparation of the IEP. Each student’s IEP will be different, reflecting their personal learning needs.

The IEP is not a legal document or a binding contract, but rather a working document. It does not require signatures.

Some students require only small adaptations or supplemental goals and minimum levels of support to achieve the expected learning outcomes for their grade level and/or courses. Some students with more complex needs will require modifications or replacement goals in their education programs. In this case some or all of their learning outcomes may differ from the curriculum.

Some students may have both adaptations and modifications in their IEPs. IEPs may be brief or detailed as appropriate and are designed to enable learners to reach their individual potential.

From school entry to school leaving, developing and implementing an appropriate IEP is critical for supporting student learning and long-term success. It’s also the foundation for reporting. Participating in the development of your child’s IEP is critical. Your role in planning, making the plan work, and ensuring that quality educational opportunities are available to your child will lead to the future you want for your child and your family.

1. Parent/Caregiver Consultation

The duty to consult with parents in the preparation of the IEP is an important statutory right. In Hewko v B.C., 2006 BCSC 1638 the BC Supreme Court held that the School Board had failed to meaningfully consult with Darren Hewko’s parents over his plan. The court held that the school district had breached its statutory duty to consult in failing to seriously consider, and where possible integrate, the parent’s home-based program as developed by the home-based consultant. There was evidence that this program could produce beneficial instruction for Darren Hewko. The District was ordered to meet its obligation by meaningfully consulting with the parents.

Meaningful consultation does not require that parents/caregivers and school staff reach an agreement. School district personnel still have the right to make decisions after they have consulted with parents/caregivers. The extent of consultation or parent collaboration will depend on the needs of the student.

These key considerations for meaningful consultation from the Surrey Schools Guide to Inclusive Education are helpful: ‘

- Parents must be consulted before any decision is made regarding the referral (e.g., psychoeducational or speech and language assessment) or placement (e.g., Connections, Social Development) of their child within the school system.

- Parents must be involved in the preparation of the IEP, PBS, Plan of Supervision, Employee Safety Plan, etc.

- Parents and the school district have a mutual obligation to provide timely information and to make whatever accommodations are necessary to affect an educational program that is in the best interests of the child.

- The parents of a child who has special needs do not have a veto over placement or the IEP. Meaningful consultation does not require agreement by either side – it does require that the school district maintain the right to decide after meaningful consultation; the above noted, an educational program or placement has the best chance of success if both school and parents are in agreement.

If you feel that your child’s IEP was developed without meaningful consultation, there are avenues for appeal. Visit the ![]() advocacy section for more information.

advocacy section for more information.

Resources: Parent Consultation

Resources: Parent Consultation

- Individual Education Plan Order

“Where a board is required to provide an IEP for a student under this order, the board… must offer a parent of the student, and where appropriate, the student the opportunity to be consulted about the preparation of an IEP.”

- Special Education Services: A Manual of Policies, Procedures and Guidelines

“Development and delivery of special education programs and services at the local level should involve meaningful consultation with the parents or guardians of students with special needs, since they know their children and can contribute in substantial ways to the design of appropriate programs and services for them.” - BC School Act (section 7 (1) and (2))

“A parent of a student of school age attending a school is entitled (a) to be informed, in accordance with the orders of the minister, of the student’s attendance, behaviour and progress in school” (7(1)) and “a parent of a student of school age attending a school may, and at the request of a teacher or principal, vice principal or director of instruction must, consult with the teacher, principal, vice principal, or director of instruction with respect to the student’s educational program” 7(2)). - Hewko v. BC (Education), 2012 SCC 61. [2012] 3 S.C.R. 360

- Supporting Meaningful Consultation with Parents (BC CAISE, 2008)

2. The IEP Process

Creating an Individual Education Plan involves three main steps:

- Developing and writing the plan.

- Implementing and evaluating the plan.

- Reporting on student progress toward the goals in the plan.

This is an evolving process. Sometimes, as the student’s needs change, the planning team changes or refines an IEP’s goals.

a. Developing an IEP

A meeting to develop an IEP usually takes place in the fall after a new teacher has had a chance to get to know the student. Parents should be invited to attend this meeting, and when appropriate the student should be included.

The team involved in the IEP needs to gather relevant information before developing a plan. This may include ![]() assessments from previous years and reports from various professionals. Sometimes parents and students will be asked to prepare for the first IEP meeting by filling in forms about the student’s interests, likes, dislikes, strengths, and stretches. Even if you haven’t been asked, it can be helpful to compile this information for the IEP meeting.

assessments from previous years and reports from various professionals. Sometimes parents and students will be asked to prepare for the first IEP meeting by filling in forms about the student’s interests, likes, dislikes, strengths, and stretches. Even if you haven’t been asked, it can be helpful to compile this information for the IEP meeting.

See also ![]() preparing for and participating in school meetings.

preparing for and participating in school meetings.

b. The IEP Meeting

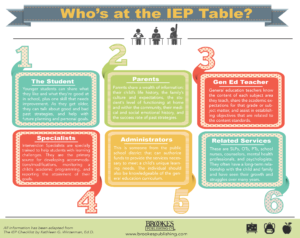

The development of the IEP involves several people that come together to make the plan for a student. In some schools, these may be the same members as the school-based team. It may include the classroom teacher, teaching assistants, learning assistants, and resource teachers and may include other community or district specialists. The IEP meeting should include parents and, where appropriate, students. Usually, a case manager coordinates and records the IEP and monitors its progress.

The Inclusion Lab at Brookes Publishing created this helpful graphic and post to describe the roles of people who are usually part of the development of a student’s IEP. A U.S.-based website, it is also best practice for developing IEPs here in B.C.

https://blog.brookespublishing.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/who-is-at-the-IEP-table.pdf

c. Tips for preparing a parent/student report for an IEP meeting

- Describe your child and outline their strengths and needs. Consider all social, educational, physical, and emotional aspects.

MyBooklet BC is a free online tool, developed by the Family Support Institute of B.C., to create a personalized information booklet for your child.

MyBooklet BC is a free online tool, developed by the Family Support Institute of B.C., to create a personalized information booklet for your child.

- Support your child describe themselves. The following resources were shared by Dr. Leyton Schnellert as part of the

Inclusive and Competency Based IEP learning series.

Inclusive and Competency Based IEP learning series.

Who am I? Profile

Who am I? Profile - “Help us get to know …” Sample profile for a student who communicates without speech.

- Describe what you want your child to learn. Include both short-term and long-term goals. The following resources will help you align the IEP goals with the redesigned curriculum:

Core competencies to help you choose competency goals.

Core competencies to help you choose competency goals.  Resources for core competency IEP goals (shared by Dr. Leyton Schnellert as part of the Inclusive and Competency Based IEP learning series).

Resources for core competency IEP goals (shared by Dr. Leyton Schnellert as part of the Inclusive and Competency Based IEP learning series).

BC Curriculum to help you prepare the curricular objectives and goals (you can search by grade and subject).

BC Curriculum to help you prepare the curricular objectives and goals (you can search by grade and subject).

- Include support documents, if necessary or relevant (for example, results of assessments, recommendations from other professionals that would be helpful to identify supports and strategies).

- Include samples of your child’s work from the previous year(s).

- If the team is new to your family and child, or you’re planning a critical transition, consider including photos or videos of your child’s home life to demonstrate your child’s skills, interests, or method of communication.

- Identify your expectations for the IEP meeting. Sometimes parents will work with the teacher or case manager before the meeting to ensure that their ideas and concerns will be addressed. You can make a list of topics you want to have addressed at the meeting and share it in advance with them to ensure they are part of the meeting plan.

Team members usually come to IEP meetings prepared to develop a working document. This meeting isn’t for making critical decisions such as those about classroom placement. Instead, the team uses the IEP meeting to identify goals and objectives for student learning and to explore strategies to support students to achieve those goals.

d. Reviewing the IEP

An IEP also includes a review process. The Ministry requires that IEPs be reviewed a minimum of once a year, but it’s sometimes possible for a student’s team to meet more often. The frequency of reviews, like the complexity of the IEP itself, will depend on the individual student’s needs.

Work with the team at your child’s school to develop a suitable plan for review meetings. Once an IEP is established, the annual review may be less extensive than the first development meeting.

The review meeting is also a good time to document what worked well, what didn’t and what everyone on the team learned about your child. This is helpful in order to pass that knowledge on to the next teaching team. This can also help to identify the need for different strategies, approaches or supports or decide if it’s necessary to reach out to other professionals.

e. Coordinating Other Student Plans with the IEP

Your child may have specific plans that address health, safety and/or behavioural issues. These may include an individualized care plan through Nursing Support Services, a positive behaviour support plan, or a safety plan. These plans are complementary to the IEP and should be coordinated with the IEP.

f. Including Transitions in the IEP

Preparing an IEP to deal with a critical transition may require more time than regular annual IEP reviews. Planning for transitions in an IEP can greatly benefit some students.

- Talk to your child’s case manager to make a plan on how to work through the transition, considering the deadlines connected to the process.

- Ask for details about deadlines, as each school district manages transitions differently.

- Document the need for any extra support in the new environment to ensure it’s in place when the transition occurs.

- See also:

Transition planning.

Transition planning.

g. After the IEP Meeting

After the IEP meeting, the case manager will create the official IEP, incorporating the key information discussed.

During the meeting, ask when you can expect to get a copy of the IEP and how you should send any comments or edits you might have. Follow up to make sure you get a copy.

The most completed version of the IEP will usually come with your child’s progress reports. An IEP must be completed in the fall of each academic year, usually around the end of November. You can confirm this deadline with your case manager or principal.

h. The following questions may help you to assess the IEP:

- Are the goals clearly stated?

- Do the goals match with the common curriculum and core competencies?

- Do the goals promote inclusion of the student?

- Was the student involved in educational planning and decision-making?

- Does the IEP presume competence and communicate high expectations?

- Do the goals prepare the student for the future?

- Do they incorporate their interests and strengths?

- Do they include all program options and extracurricular opportunities?

- Are there both long-term and short-term goals?

- Are the people responsible for helping meet the goals noted?

- Does the IEP include a list of additional services required, such as speech and language/occupational therapy?

- Are upcoming transitions incorporated into the IEP?

- How will my child’s progress be measured or evaluated, and by whom?

- How will we know when the goals have been reached?

- Is there a review date set?

i. IEPs and SMART goals

The previous version of this handbook included a section dedicated to SMART goals. This way of assessing IEP goals started with a student’s deficits and identified ways to address them through instruction. In ![]() “See Ya Later SMART Goals,” Shelley Moore explains what’s wrong with the traditional approach and presents new, child-focused and strength-based SMART goals. See

“See Ya Later SMART Goals,” Shelley Moore explains what’s wrong with the traditional approach and presents new, child-focused and strength-based SMART goals. See ![]() Five Moore Minutes and the Resources section for more resources from Shelley Moore.

Five Moore Minutes and the Resources section for more resources from Shelley Moore.

Shelley Moore’s (Moore, 2021) new acronym for SMART goals asks, is the IEP:

- Strength-based

- Meaningful

- Authentic

- Responsive

- Triangulated

j. Implementing and evaluating the IEP

The school must ensure that all supports are in place before the IEP is implemented. It’s also critical that everybody involved in the planning understands and supports the plan.

Implementation works best when it incorporates an ongoing assessment of the plan to refine or validate the goals and strategies. The plan will require collaboration among members of the school community and may also require support from other government ministries or community agencies.

It is helpful to establish a communication plan that will help with implementation. For example, what is the best way to communicate with the teacher? When should you contact the case manager?

It’s important to seek clarity and be clear on preferred methods of communication, roles, responsibilities and expectations of everyone involved. If you’re not 100% sure, ask the case manager to avoid assumptions.

See also: ![]() Preparing for and Participating in School Meetings

Preparing for and Participating in School Meetings

Implementing an IEP is most successful when the team starts with the strengths of the student, and not their needs or deficits.

3. Reporting on student progress

All students receive report cards at the same time. Parents must receive a minimum of five reports describing a student’s progress throughout the school year. Three of those reports will be formal written reports, including a summative report at the end of the year. The other two can be more informal like phone calls, student-led conferences, parent-teacher conferences, using journals, or emails. More than being formal or informal, the expectation is that reporting is timely and responsive throughout the school year, following each district’s policies and procedures.

With changes in the curriculum, there are also changes in the way to report students’ progress. For Grades K-9, students receive reports including a performance scale and description of progress in relation to the learning goals of the curriculum and/or goals in their IEP. For Grades 10-12, the formal reports include letter grades, percentages, and written reporting comments.

Students with adaptations or supplemental goals are evaluated in the same way as their typical peers. Students with modified programs or replacement goals are evaluated on their progress, and reporting should note the degree to which they’ve achieved the goals of their IEP.

Regardless of whether a student has an adapted or modified program, reporting must reflect the student’s progress in developing their individual potential.

For students with modified goals, the most appropriate form of reporting should be determined collaboratively at the school level. The report refers to the goals and objectives established in the IEP and reflects the student’s progress toward those goals. (There is a discussion of graduation credentials in the section called “Acknowledging student success: Graduation” later in this chapter).

It is important to have a conversation every year with your child’s teacher about how their learning will be evaluated and reported. A student with an IEP, even if they have modifications or replacement goals, should receive the same type of reports as their peers. The redesigned curriculum considers a wide range of learners and every student can fit in the performance scale.

![]() Student Reporting (Ministry of Education)

Student Reporting (Ministry of Education)

4. Student Learning Plan (or Student Support Plan)

Students who do not have a Ministry designation but do have additional support needs may have a student learning plan (SLP) (some districts may call this a student support plan). An SLP usually fulfills the same purpose as an IEP but it is not governed by the School Act in the same way as an IEP is.

Much of the information in this handbook may also apply to a student learning plan.

All students are entitled to the support they need to access an education. While schools may not receive supplemental funding for a student who does not have a designation or diagnosis, districts are required to support all learners. All school districts receive the Basic Allocation funding to help them support all students. The K-12 Funding – Special Needs policy reads:

“The Basic Allocation, a standard amount of money provided per school age student enrolled in a school district, includes funds to support the learning needs of students who are identified as having learning disabilities, mild intellectual disabilities, students requiring moderate behaviour supports and students who are gifted.” Ministry of Education Policy: K-12 Funding – Special Needs

5. Competency-Based Individual Education Plan

Many school districts across BC have begun to use a Competency-Based Individual Education Plan (CB-IEP). This new CB-IEP is intended to align with the ![]() core and curricular competencies of the redesigned curriculum.

core and curricular competencies of the redesigned curriculum.

The traditional IEP was designed for students with disabilities and additional support needs who were learning in self-contained settings with other students who also had IEPs. Their learning goals did not align with the common curriculum. The CB-IEP is designed for inclusive classrooms following the redesigned curriculum, providing an entry point to the curriculum for all students, whatever their ability. To understand the Competency-Based IEP, it’s important to understand the basic tenets of BC’s redesigned curriculum. (see ![]() Redesigned Curriculum section in Chapter 4)

Redesigned Curriculum section in Chapter 4)

The CB-IEP is in its early stages, and not all school districts are using it consistently. Inclusion BC and other advocates have asked the BC Ministry of Education to update its Special Education Policy Manual to reflect the CB-IEP. An updated policy document will help ensure consistency and best practice, providing educators and parents/caregivers with the information they need to implement the new CB-IEP consistently and successfully.

Ask your school team if the district is using the Competency-Based IEP or if/when they plan to start using it. At the end of this chapter are some resources to help you and your school team make the most of the CB-IEP.

a. Presuming Competence

The Competency-Based IEP presumes competence. It starts with the premise that all students can learn, regardless of how they’re communicating or how they’re accessing knowledge. This shift in thinking rejects old methods of collecting and relying on data based only on what kids cannot do. It recognizes that ability and learning can take many forms and look unique to every student.

“Presuming Competence is simply believing and trusting that all students can learn and all students can get something out of any and all placements – even Physics 12.” (Shelley Moore)

b. Student Agency

Student agency is at the heart of the redesigned curriculum and competency-based IEPs. Historically students have been left out of the IEP process, with little or no ownership over their learning. The CB-IEP puts the student’s voice at the centre.

Importantly, this does not mean that parents can or should be excluded in the development of the IEP. A ![]() parent’s right to consult is still crucial.

parent’s right to consult is still crucial.

“This new format is designed to encourage student voice as active participants in IEP development, and link learning to the development of the core and curricular competencies of our redesigned BC Curriculum” (Richmond SD 48)

![]() Video Exercising Self Determination in Our Schools (Inclusion BC, 2021)

Video Exercising Self Determination in Our Schools (Inclusion BC, 2021)

6. Adaptations and Modifications

While many school districts have started using a ![]() Competency-Based IEP, neither the 2009 BC Ministry of Education policy document “Guide to Adaptations and Modifications” nor the Special Education Policy Manual have been updated. These documents therefore still apply and the previous version of the IEP is still being used in many districts.

Competency-Based IEP, neither the 2009 BC Ministry of Education policy document “Guide to Adaptations and Modifications” nor the Special Education Policy Manual have been updated. These documents therefore still apply and the previous version of the IEP is still being used in many districts.

a. Adaptations

Adaptations are developed and implemented when a student’s learning outcomes are expected to exceed or be the same as those described in the provincial curriculum.

There is a range of adaptations that can help create meaningful learning opportunities and evaluate student progress.

Adaptations may include:

(from A Guide to Adaptations and Modifications, B.C. Ministry of Education)

- audio tapes, electronic texts, or a peer helper to assist with assigned readings

- access to a computer for written assignments (e.g. use of word prediction software, spell‐checker, idea generator)

- alternatives to written assignments to demonstrate knowledge and understanding

- advance organizers/graphic organizers to assist with following classroom presentations

- extended time to complete assignments or tests

- support to develop and practice study skills; for example, in a learning assistance block

- use of computer software which provides text to speech/speech to text capabilities

- pre‐teaching key vocabulary or concepts; multiple exposure to materials

- working on provincial learning outcomes from a lower grade level

Reporting for students with adapted programs follows ministry grading and reporting policies for the regular K–12 program. Students with adapted programs receive letter grades in the intermediate and high school years.

The IEP notes any adaptations that apply to evaluation procedures. However, official transcripts need not identify those adaptations.

Students whose IEP includes adaptations and not modifications will usually be eligible for a Dogwood Diploma.

There is a range of adaptations that can help create meaningful learning opportunities and evaluate student progress. The new Competency-Based IEP uses “supports for access” to describe supports and strategies that are universal (available to all students) and essential (identified through testing and necessary for a student to access the curriculum).

- Example of Universal and Essential Supports for Access from Resource from Inclusive Competency Based IEP workshop series, Session 8 with Dr. Julie Cawston.

- Example of Adaptations and Modifications from A Guide to Adaptations and Modifications, Ministry of Education.

b. Modifications

“The decision to use modifications should be based on the same principle as adaptations—that all students must have equitable access to learning, opportunities for achievement, and the pursuit of excellence in all aspects of their educational programs.” Ministry of Education, A Guide to Adaptations and Modifications

Formal decisions on whether a program, or part of a program, includes modifications should not be made before grade 10 (A Guide to Adaptations and Modifications, Ministry of Education).

Modifications involve setting goals that differ from those in the provincial curriculum. Every effort should be made to support the student to access the learning goals of the curriculum before deciding to use modifications. Particularly in the elementary school years, and should continue into middle and secondary years. The redesigned curriculum allows for access points for a wide range of learners through the ‘big ideas’ of each course.

The decision to modify the goals of the curriculum will often mean that the student receives a School Completion Certificate, called Evergreen Certificate, instead of a Dogwood Diploma, B.C.’s graduation credential. Students who receive an Evergreen have not graduated. This major decision should include the informed consent of the student’s parent/guardian.

See ![]() Acknowledging Student Success: Graduation section below for more details.

Acknowledging Student Success: Graduation section below for more details.

7. Academic or life skills?

Myth: Your child doesn’t need to learn academics. For children like yours, it’s better to concentrate on life skills.

When IEPs are modified, teachers need to set goals that are high but attainable. Modified IEPs should include academic skills to the greatest possible extent while keeping goals attainable so that learners can succeed. The goals should address all aspects of learning and may include the following:

- academic skills

- independent living skills

- participation in community activities

- personal safety, health, and relationship skills (should address sexuality and sexual development for a healthy life, which can reduce vulnerability to mistreatment)

- self-management and decision making

- career planning and work experience

Though “life skills” are important, they shouldn’t form the basis of the entire educational program. Research shows that people with disabilities and additional support needs who have more education also have better life outcomes. Life skills can be learned throughout life in a variety of places, but for many students, school will provide their best opportunity to develop academic skills.

8. Graduation Requirements and Transcripts

The IEP notes any adaptations or supports that apply to evaluation procedures. However, official transcripts need not identify those adaptations. It is important to document on the IEP the adaptations or supports that best support your child’s learning.

When the time comes for the ![]() Provincial Graduation Assessments, students who need supports will go through an adjudication (approval) process to have those supports available during the assessments. The supports would be the same that have been provided to the student in the classroom setting.

Provincial Graduation Assessments, students who need supports will go through an adjudication (approval) process to have those supports available during the assessments. The supports would be the same that have been provided to the student in the classroom setting.

Resources: Adjudication and Exam Adaptations

Resources: Adjudication and Exam Adaptations

- B.C. Graduation Program Handbook of Procedures [ch2] (Ministry of Education)

“As a part of the adjudications process, schools (public and independent) or school districts must:- Determine if a student has a demonstrated need for supports.

- Ensure all decisions regarding supports are based on evidence documented in the student’s file (Individual Education Plan [IEP] or Student Learning Plan [SLP]).

- Ensure a master list of all students receiving supports is kept on record at the School District Office. Districts are required to maintain a list of students and the supports received for a period of five years.”

- Adjudication: Supports for Graduation Assessments (Ministry of Education)

- Guidelines: Provincial Assessment Adjudication (BC Graduation Program Policy Guide)

9. Graduation: Evergreen Certificate or Dogwood Diploma

Leaving school and entering adult life is a much-celebrated event for youth. An important part of marking the achievements of students with disabilities and additional support needs who complete high school is participating in all aspects of graduation.

All students should be included in formal ceremonies, proms, and related festivities. This is the essence of inclusion.

![]() Resource: How to Make Your Event More Inclusive (Inclusion BC) This resource may be helpful for graduation planning committees.

Resource: How to Make Your Event More Inclusive (Inclusion BC) This resource may be helpful for graduation planning committees.

All students should also receive recognition and rewards for their learning achievements. Students with disabilities and additional support needs should be acknowledged and rewarded for their achievements alongside their peers. This recognition should arise from the wider community’s acknowledgment of the importance of inclusion.

Currently, the BC Ministry of Education issues official documents that acknowledge the accomplishments of all graduating students. All students who successfully complete the provincial graduation requirements (80 credits and Provincial Graduation Assessments), receive Dogwood Diplomas.

Students with modified IEPs who complete their educational programs, as established in their IEP, receive a B.C. School Completion Certificate called the Evergreen Certificate. A school board must recommend to the Minister that a student be awarded a School Completion Certificate.

School districts report to the Ministry on the achievements of students with modified IEPs in the same way that they do with all students and transcripts are issued.

Students who graduate with an Evergreen Certificate can study to receive an Adult Dogwood Diploma after they turn 18. These courses are offered free to B.C. residents by various post-secondary institutions or school district continuing education centres. An Adult Dogwood is equivalent to a regular Grade 12 diploma and is accepted by employers and post-secondary institutions.

![]() While there are no prerequisites, there are certain grade 10 courses that will prepare the student for the required grade 11 and 12 courses. (Read more about the Adult Dogwood)

While there are no prerequisites, there are certain grade 10 courses that will prepare the student for the required grade 11 and 12 courses. (Read more about the Adult Dogwood)

- Certificates of Graduation (Dogwood Diploma)

- School Completion Certificate Program (Evergreen Certificate)

10. “Grade 13”

The B.C. School Act defines “school age” as follows:

the age between the date on which a person is permitted under section 3 (1) (of the School Act) to enroll in an educational program provided by a board and the end of the school year in which the person reaches the age of 19 years.

A student remains “school age” until the school year in which they reach the age of 19 years. If a student turns 19 on July 1 or later, they are eligible to enroll in school the following September.

Many students with disabilities and additional support needs choose to stay for what is often referred to as the “over-age year” or “grade 13.” This is not an “extra year” of education but is a year in which a student remains eligible to attend.

A student must be offered a full-time educational program (with an IEP where applicable) during the year in which they turn 19. Students who have an IEP, need adaptations or supplemental supports, and are pursuing a Dogwood Diploma may be eligible to remain in school until they’re 21.

The Ministry of Education continues to provide funding to the school board for students with disabilities and additional support needs at the same level as they have in all previous educational years.

Many students with disabilities and additional support needs use the final year of education to focus on community and transition planning.

11. Resources: Individual Education Plans

11. Resources: Individual Education Plans

- Special Education Services: A Manual of Policies, Procedures and Guidelines BC Ministry of Education, 2016.

- A Guide to Adaptations and Modifications Ministry of Education, 2009.

- This document was published by the B.C. Ministry of Education and developed in consultation with groups representing educators in the school system.

- Individual Education Plans: A Guide for Parents BCCPAC, 2014 (available in several languages).

- Transitioning to High School BC Centre for Ability, 2021.

- The Transitions Timeline from the Family Support Institute of B.C. on their findSupportBC website .

- MyBooklet BC from the Family Support Institute of B.C. is a free online tool to create a personalized information booklet for your child.

- Individual Education Plans & Student Support Plans Surrey Schools, 2021.

- Inclusive and Competency Based IEPs Shelley Moore, 2020.

- See Ya Later S.M.A.R.T Goals (Video) Shelley Moore, 2019.